By Xiaopeng Zhang | February 12, 2021

FortiGuard Labs Threat Research Report

Affected platforms: Microsoft Windows

Impacted parties: Windows Users

Impact: Control and Collect sensitive information from victim’s device, as well as delivering other malware.

Severity level: Critical

FortiGuard Labs recently detected a suspicious email through the SPAM monitoring system that was designed to trick a victim into opening a web page to download an executable file. Additional research on this executable file found that it is a new variant of the Bazar malware.

My analysis of this variant is being published in two parts. In the first part of the analysis, I explained how the Bazar loader was downloaded onto a victim’s device, how it communicates with its C2 server to obtain a Bazar file, and how that file is then injected into a newly-created “cmd.exe” process.

In this second part, I will focus on the Bazar payload file that runs inside the “cmd.exe” process. You will learn what new anti-analysis techniques this Bazar uses, how it communicates with its C2 server, what sensitive data it is able to collect from the victim’s device, and how it is able to deliver other malware onto the victim’s system.

Main() function of the Bazar Payload

This variant of the Bazar payload is a 64-bit executable file written in Microsoft Visual C++ 8.0. It was compiled on Monday, Jan 18, 2021.

In its Main() function, we can see that it is driven by a “Timer” set by the API SetTimer() and then captured by GetMessageA(). When a condition is matched, the working function is called once. The pseudocode of how they work together is shown in Figure 1.1, below.

Figure 1.1. Pseudocode of the Main() function of Bazar

Anti-analysis Techniques

I also observed three primary anti-analysis techniques being used throughout entire Bazar execution. I will explain how each of these work.

1. All key APIs are hidden

Bazar hides key APIs in the code and only uses them when it needs to call. A function that I call get_api() is used to dynamically get an API address with the API name hash and its module index. The API address is carried in the RAX register when get_api() returns. More than 600 APIs are obtained in this variant by using get_api(). Analyzing this API is complicated because nobody is able to read it via its name hash code. This really creates trouble for researchers during both dynamic and static analysis.

The piece of ASM code shows below when it retrieves the API “TerminateProcess” with the name hash 0x9E6FA842 and module index 8. As stated earlier, the address is found in RAX when the API call returns.

xor ecx, ecx

mov edx, 1

mov r8d, 9E6FA842h ; The hash of API “TerminateProcess”.

mov r9d, 8 ; An index of the module that contains “TerminateProcess”.

call get_api

mov [rsp+698h+var_640], rax ; “TerminateProcess” is in RAX.

2. ASM Code Obfuscation

If you are curious about the code structure, the pseudocode (shown in Figure 1.1) looks so weird because Bazar uses a kind of code obfuscation technique. This is another barrier to threat researchers in clearly tracking the code. Here is an example of how the ASM code is obfuscated.

The original code is below:

mov [rsp+40h+var_18], rdx

mov rbp, [rsp+40h+var_18]

cmp rbp, 4

jae Lable_1

mov rdx, [rsp+40h+var_18]

movzx ebp, [rsp+rdx+40h+var_10]

imul ebp, -0Bh

mov ebx, ebp

add ebx, 273h

[…]

Lable_1:

lea rcx, [rsp+40h+arg_40]

lea rdx, [rsp+40h+var_10]

call sub_13F944B2E

After obfuscation, it becomes this (the original code is highlighted):

mov ecx, 370A6DACh

Label_0:

mov [rsp+40h+var_18], rdx

mov rbp, [rsp+40h+var_18]

cmp rbp, 4

mov ebp, 0B03F61D0h

cmovb ebp, ecx

jmp Label_1

[…]

Label_1:

cmp ebp, 0F7C9568Bh

jg short Label_2

cmp ebp, 0B03F61D0h

jz Label_3

cmp ebp, 0BAE74C5Ch

jz Label_5

cmp ebp, 0EC1D9526h

jnz short Label_1

jmp Label_4

[…]

Label_2:

cmp ebp, 0F7C9568Ch

jz Label_6

cmp ebp, 2BA792A4h

jz Label_0

cmp ebp, 370A6DACh

jnz short Label_1

mov rdx, [rsp+40h+var_18]movzx ebp, [rsp+rdx+40h+var_10]imul ebp, -0Bh

mov ebx, ebp

add ebx, 273h

[…]Label_3:

mov ebp, 0EC1D9526h

jmp Label_1

[…]Label_4:

lea rcx, [rsp+40h+arg_40]lea rdx, [rsp+40h+var_10]call sub_13F944B2E

As you can see, the obfuscated ASM code was mixed with huge amounts of trash-like code while also becoming quite sophisticated in its logic. Almost every function in Bazar has had this kind of obfuscation approach applied.

3. All constant strings are encoded in Bazar

Another form of obfuscation affects the use of constant strings. Bazar’s constant strings are hidden in encrypted data throughout the code to perform anti-analysis.

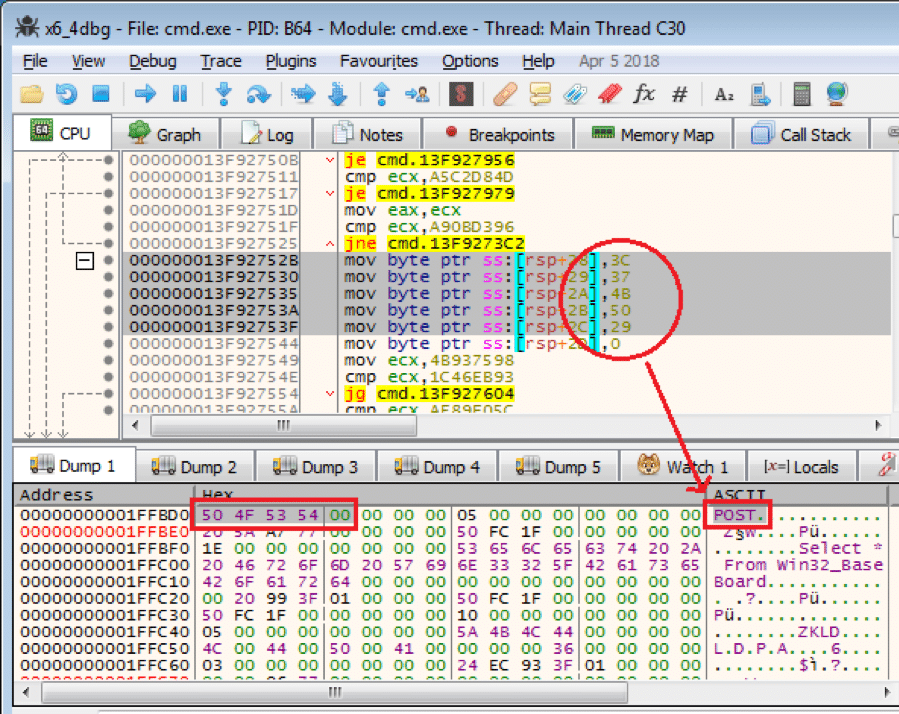

Figure 2.1. Just decrypted a constant string “POST”

According to Figure 2.1, the encrypted data (“3C 37 4B 50 29”) was copied from the stack and decrypted to “POST” before using it.

Communicating with the C2 Server

In its working function, after Bazar does some initial work, such as setting environment variables, creating mutex objects, loading APIs and setting global variables, it creates a thread to perform its tasks in the thread function.

The thread function connects to the C2 server and sends data to it. The C2 server host strings are decrypted constant strings. They are “miraclecarwashanddetall[.]com:443″ and a group of additional hosts: “caexidom[.]bazar”, “ektywyom[.]bazar”, “emliwyyw[.]bazar”, “uhymeked[.]bazar”, “ibykwyyw[.]bazar”, and “elicuhem[.]bazar”. Bazar prioritized connecting to the first C2 server host. It then attempts to connect to the others if the first one does not work.

1. Request

The traffic between Bazar and its C2 server is encrypted via SSL protocol. The following image, Figure 3.1, was taken when the first request was about to be SSL-encrypted by calling the API EncryptMessage().

Figure 3.1. Bazar encrypts a packet via the SSL protocol

As you can see, this is a GET request. The URL “/cgi-bin/req5” is a decrypted constant string, and the host is the first C2 server I mentioned above. There are also four “Cookies”: “fpzkgo”, “bcfs”, “hky” and “otxe”. Their names are random strings and only the value of “fpzkgo” is valid data. The others are random data.

Let’s take a look what the value of “fpzkgo” consists of. According to my analysis, it has two parts, the Victim-ID and a command number. The Victim-ID for my testing device is “a9aadd987308f3a5b28d5a0c552c4324”. That is an MD5 hash code of a string of information obtained from my device, such as the computer name, the volume number of the partition, and Windows installation information.

The format of the report command is “/{Victim-ID}/{command number}”. The first “GET” packet’s command number is “2”. Therefore, the final command string is “/a9aadd987308f3a5b28d5a0c552c4324/2”.

Bazar then encrypts the command string in a 100H buffer using a private key encryption technique that uses the RSA algorithm. Figure 3.2 shows both the plaintext data at the top and the cipher text at the bottom.

Figure 3.2. Using the RSA algorithm to encrypt the Victim-ID and command string

Finally, Bazar base64 encodes the RSA encrypted data, which is the value of the “Cookies” item “fpzkgo”, as shown in Figure 3.1.

All the command packets to the C2 server are enclosed in “Cookies” and use the same steps and algorithm to generate.

2. Response

Once the C2 server receives and handles the malware request and notification, it replies to Bazar. So, in this section, we will analyze the response packet. Referring to Figure 3.3, you can see in the memory section that one response packet had just been decrypted from a SSL packet using the API, DecryptMessage().

Figure 3.3. Display of received response packet

This response packet includes the item “Set-Cookies: jklo=…” in the header, whose value is base64 encoded. After base64 decoding the value, Bazar gets an RSA-encrypted 100H long set of data. Using the C2 server’s public key, Bazar is able to decrypt this data set to get to the command string from the C2 server. Figure 3.4 shows the RSA decrypted command string, “0 302”, uncovered by calling the API BCryptDecrypt().

The “0” of “0 302” is the command number, and “302” is the command data.

Figure 3.4. A decrypted C2 command string from the “Set-Cookies” item

This is pretty much the basic packet structure used for all other communication packets between Bazar and C2 server. I will talk about more control commands in next section.

Analyzing the Command and Control (C2)

Bazar is able to control the victim’s device with the commands it receives from the C2 server. In the previous section, I identified the C2’s command “0” in the “0 302” string. By going through Bazar’s code, I have been able to identify that it supports the following C2 command numbers: “0”, “1”, “10”, “11”, “12”, “13”, “14”, “15”, “16”, “17”, “18” and “100”.

In this section, I explain some of the known commands used in this malware, including what the command packet consists of and the purpose of those commands being used.

When Bazar needs to send whichever data the C2 server requests, it sends a “POST” request with the URL “/cgi-bin/req5”, the command number string enclosed in “Cookies”, and the RAS-encrypted data in the “body” of the request.

As a reminder, the format of the report command is “/{Victim-ID}/{command number}” and the Victim-ID for my test device is “a9aadd987308f3a5b28d5a0c552c4324”.

Command 0:

The C2 server asks Bazar to send the host string and port it is connecting to and the running time of Bazar on the victim’s device. Below is an example of this data.

“rnVerBD 205rnmiraclecarwashanddetall.com:443rnuptime 232“. Bazar encrypts it using its private key as the data in the “body” of the “POST” it sends to the C2 server.

“/a9aadd987308f3a5b28d5a0c552c4324/4” is enclosed in “Cookies” to provide the Victim-ID and command number.

Command 1:

This command asks Bazar to collect data from victim’s system, like OS information, domain, user name, public IP address, location and language, all software installed, network information, shared folders, a list of running processes, time zone, CPU information, hard drive capacity, physical memory capacity, and whether Bazar is running in a VM.

It calls the APIs GetVersionExA() and GetProductInfo() to obtain the Windows’ Version and Service Pack information.

To obtain the public IP address of the victim’s device, Bazar sends a STUN request (UDP packet) to one of Google’s STUN servers, such as “stun2.l.google.com”, to retrieve the public IP address. Figure 4.1 is a Wireshark screenshot of the command requesting Bazar to send the STUN packet.

Figure 4.1. Obtaining the victim’s public IP address using the Google STUN service.

Bazar executes several commands to obtain network related information and domain trusts from the victim’s device. The commands are “net view /all”, “net view /all /domain”, and “nltest.exe /domain_trusts /all_trusts”.

It then enumerates the system registry to collect the list of installed software on the victim’s device. Figure 4.2 is a screenshot of the system registry showing a partial list of installed software under the sub-key “HKLMSOFTWAREMicrosoftWindowsCurrentVersionUninstall”.

Figure 4.2. Software information installed on the victim’s device

Bazar calls APIs CreateToolhelp32Snapshot(), Process32First(), Process32Next(), and OpenProcess() to collect information about the running processes on the victim’s system.

Bazar also performs some WMI query strings, such as “Select * From Win32_Processor”, “Select * From Win32_DiskDrive”, and “Select * From Win32_PhysicalMemory” to obtain information about the CPU, drive, and physical memory.

It obtains hard disk description from “HKLM SYSTEMCurrentControlSetServicesDiskEnum” in the system registry. For my research environment (Oracle VM VirtualBox), it is “IDEDiskVBOX_HARDDISK___________________________1.0_____5&33d1638a&0&0.0.0”. Bazar then searches for the key words “VBOX” and “VMware” to determine if Bazar is running on a VM.

When this collection is done, it sends all of the gathered information in the “body” of the “POST” request to the C2 server. The report command string “/a9aadd987308f3a5b28d5a0c552c4324/3” is enclosed in “Cookies”. The image in figure 4.3 shows the malware when it is about to encrypt the collected data by calling BCryptEncrypt().

Figure 4.3. RSA algorithm used to encrypt the collected sensitive information from the victim’s device.

Command 10, 11:

These commands could contain a link to download other malware, or it could contain the malware directly. Bazar injects this malware into one of the newly-created processes in the following list, which are decrypted constant strings.

“c:windowssystem32calc.exe”

“c:windowssystem32cmd.exe”

“c:windowssystem32notepad.exe”

“c:windowssystem32svchost.exe”

“c:windowssystem32explorer.exe”

“c:windowssyswow64calc.exe”

“c:windowssyswow64explorer.exe”

“c:windowssyswow64cmd.exe”

“c:windowssyswow64svchost.exe”

“c:windowssyswow64notepad.exe”

It then gives the C2 server a status update by replying with a message of “file not downloaded”, ”loader started”, ”program is running”, or ”program start error” in a “POST” request together with a report command string of “/a9aadd987308f3a5b28d5a0c552c4324/3”.

Command 12, 13:

C2 server replies with a script file to Bazar in a command. Bazar then decrypts the script file and saves it to a Windows temporary folder. Finally, Bazar runs it by calling the API CreateProcessA().

Bazar notifies the C2 server of the status of the script by replying with a message of “program is running” or an error message of “program start error”, ”no script”, or ”no memory” when an error occurs.

The message is RSA-encrypted and posted as the “body” data of a “POST” request together with a report command string of “/a9aadd987308f3a5b28d5a0c552c4324/3” enclosed in a “Cookies” value.

Command 16:

Bazar reads a file path from the C2 server’s command and collects the file’s contents. It sends the collected data as the “body” of a “POST” request to back to the C2 server.

The report command string is “/a9aadd987308f3a5b28d5a0c552c4324/3”.

Command 17:

The C2 server replies with a piece of native code that has been RSA-encrypted in the command. Bazar decrypts the native code (ASM code) using the C2 server’s public key and deploys it on a newly-create thread to execute. To achieve this, it needs to call some APIs, such as VirtualAlloc(), memcpy(), VirtualProtect(), and CreateThread(). Figure 4.4 provices a partial view of the relevant ASM code.

Figure 4.4. A code snippet of Bazar handling received native code.

As with other commands, it also replies with a status to the C2 server in a same way. The messages could be “program is running” or an error status like “no code”, “no memory”, and “program start error”, etc.

Command 100:

When Bazar receives this command, it terminates itself by calling the API TerminateProcess().

Conclusion

The second part of this analysis is all about the Bazar payload that was downloaded by the Bazar loader. I have shown the three primary anti-analysis techniques used by this Bazar variant. Furthermore, I also showed how Bazar communicates with the C2 server, what control commands Bazar supports, as well as what malicious things Bazar is able to do on a victim’s device with those commands.

At this moment, this particular Bazar’s phishing campaign is still active and are frequently being captured by FortiGuard Labs.

Fortinet Protections

Fortinet customers are already protected from this Bazar variant with FortiGuard’s Web Filtering and AntiVirus services as follows:

The Bazar loader download URLs are rated as “Malicious Websites” by the FortiGuard Web Filtering service.

The downloaded files are detected as “W64/Bazar.CFI!tr” and blocked by the FortiGuard AntiVirus service.

The FortiGuard AntiVirus service is supported by FortiGate, FortiMail, FortiClient and FortiEDR. The Fortinet AntiVirus engine is a part of each of those solutions. As a result, customers who have these products with up-to-date protections are protected.

We also suggest our readers to go through the free NSE training — NSE 1 – Information Security Awareness, which has a module on Internet threats designed to help end users learn how to identify and protect themselves from phishing attacks.

IOCs:

URLs

hxxps[:]//miraclecarwashanddetall[.]com:443/cgi-bin/req5

hxxps[:]//caexidom[.]bazar

hxxps[:]//ektywyom[.]bazar

hxxps[:]//emliwyyw[.]bazar

hxxps[:]//uhymeked[.]bazar

hxxps[:]//ibykwyyw[.]bazar

hxxps[:]//elicuhem[.]bazar

References:

https://malpedia.caad.fkie.fraunhofer.de/details/win.bazarbackdoor